Bukele Claims Economic Prosperity, But Economist’s Data Shows Otherwise

While Bukele has spent several years on an intense, multimillion-dollar international propaganda campaign to convince the world that he has transformed El Salvador into some kind of paradise, working families are experiencing a bleak economic reality. Popular discontent regarding economic woes, especially the rising cost of food, has grown such that the Bukele regime was pressured to address it head on, giving a July 5 national television address on the current economic crisis, the first of several. However, economists and popular movement organizations say the measures he’s proposed will do nothing to address the crisis his own policies are causing and are calling instead for genuine solutions such as increases to the minimum wage, support for national agriculture, and adequate funding to education.

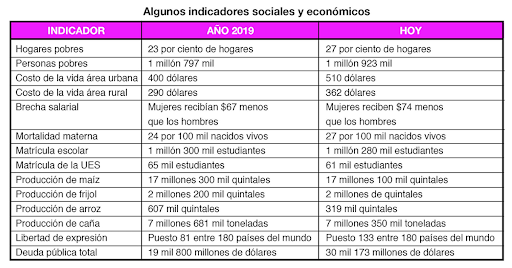

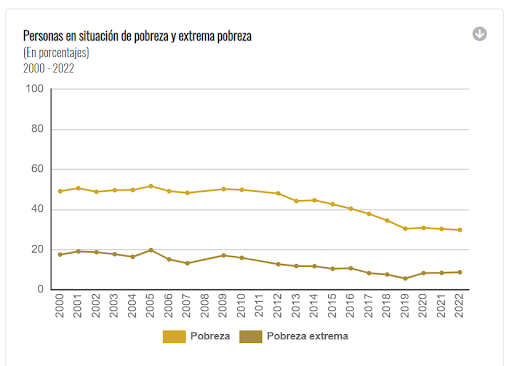

Since 2019, when Nayib Bukele took office, the poverty rate has risen from 23% to 27% of households experiencing poverty, according to recent statistics shared by the popular education collective, Equipo Maiz (see below). Data from the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (CEPAL) also show that extreme poverty is on the rise (see below), which the Central American Fiscal Institute describes “a reversal of nearly a decade in the fight to eliminate extreme poverty.” In that same time period, underemployment has climbed, and over 130,000 jobs have been lost in key sectors such as agriculture, manufacturing, social services, health, and education.

Chart: Equipo Maíz, 5/31/24

Graphic: CEPAL’s National Social-Demographic Profile of El Salvador

Meanwhile, prices for basic foods have increased, purchasing power has decreased, and food insecurity has worsened, with nearly half the population “not eating enough on a daily basis,” according to a report from the UN’s Food and Agricultural Organization. Since the start of Bukele’s presidency in 2019, the cost of the canasta básica, or monthly food basket, has risen from $200 to $246 in urban areas and from $144 to $183 in rural areas. For reference, $183 per month is 72% of the average monthly minimum wage for agricultural workers in rural areas ($253).

Inflation in food costs throughout Bukele’s first term has deepened the economic woes Salvadoran families face. In a recent article, La Prensa Gráfica calculated that the 10.82% rise in food costs in El Salvador since June 2022 is the highest rate among dollarized countries in the hemisphere within the same period, above the U.S. (8.09%), Ecuador (6.14%) and Panama (4.47%). A spike in recent weeks seems to have contributed to the pressure leading to Bukele’s public response. Within the last two weeks of June, for example, the cost of pipian (a green squash) rose 233%, for example, while the cost of potatoes rose 88% and tomatoes 65%, according to data from the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock.

Part of the food insecurity challenge is El Salvador’s increasing reliance on imported goods, as funding and support for the domestic agriculture sector has dropped perilously under Bukele: between 2019-2023, rice production dropped over 37%, while fruit production dropped 35% and vegetable production 14%. As international news outlets have reported, “Government data show that El Salvador imports 90% of legumes, vegetables and fruits and the majority of the other basic products in the basket are purchased from neighbors like Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua to meet the local demand. Sixty percent of milk products are imported along with 25% of beans and 33% of rice that the population needs.”

A closer look at Bukele’s proposed “solutions”

The high price of food was the major issue that Bukele claimed he would “tackle” in his July 5 speech on the national television station. He blamed importers for the crisis, accusing them of price gouging and threatening them with arrests. As Salvadoran law only allows fines or administrative sanctions - not criminal prosecution - for price “abuses,” he instead threatened to prosecute importers for known instances of tax evasion, bribery and contraband if they didn’t lower prices, though apparently not otherwise.

As various commentators have noted, his bombast echoed his threats against the gangs, saying, “We aren’t playing, and if anyone says this is just an empty threat, a show, a smokescreen, well, they’ll see if it’s just a smokescreen. The gangs said the same thing. I expect lower prices tomorrow or you’re going to have problems.”

Days later, Bukele also announced a plan to eliminate tariffs on all 70 foods that make up the basic food basket for the next ten years. Economists and community organizations quickly pointed out, however, that this measure is also a non-solution, given that “there are already no tariffs on staple foods (such as tortillas, French bread, and sugar). For others, such as beans, rice, vegetables, fruit, and meat, a certain amount is imported, but they are not subject to tariffs because they are purchased from Central America, the United States, Mexico, and other countries with whom there are free trade agreements that have eliminated tariffs. Taxes have already been removed for many products.”

The government of Guatemala, which, alongside Nicaragua and Guatemala, provides 89% of the staple foods imported into El Salvador, affirmed this reality in a July 23 statement, saying, “In Central America, there is already free trade for basic foodstuffs and they enter the market without tariffs” as a result of previously negotiated trade agreements.

Popular movement organizations and associations representing small and medium producers have countered that the solution to food instability is to reinvest in domestic agriculture. As the Popular Rebellion and Resistance Bloc (BPR), a grassroots coalition of student, labor, and community organizations, wrote in a July 21 statement, “Bukele's announcement [about eliminating tariffs] is simply another lie. If he is really interested in solving the problem of rising food prices, he should announce an agricultural development program that increases production and provides agricultural inputs, credits, and technical assistance so that more basic grains, vegetables, fruit, dairy products, and meats are produced throughout the country.

“The truth is that [Bukele’s] measures respond to the deceptive neoliberal idea that it is cheaper to import than to produce. Bukele is not thinking about domestic producers, much less about the consumer population that suffers every day from the increase in prices. His goal is to favor large importers, which are his business partners and political allies.” (Read the full statement here in Spanish and here in English)

Labor unions and popular movement organizations have also made clear that another effective component of addressing food insecurity and other economic difficulties would be to significantly increase the minimum wage. The minimum wage in El Salvador is currently $364 for commercial, industrial, and service workers; it’s even lower for maquila workers and domestic workers ($359), coffee and sugarcane workers ($273), and other agricultural workers ($243). This falls far short of the average monthly expenses for a family, including food, housing, utilities and other essentials, which the Center for the Defense of the Consumer calculates to be $914 in 2024, up 23% from 2019. For comparison, the average minimum wage in neighboring Guatemala is $456 and in Honduras, $538.

The labor code requires the minimum wage to be increased every three years, including this year, and unions and other social movement organizations are already preparing for an uphill battle to win the increases needed to allow the poor majority a more dignified life. The minimum wage is set by a National Minimum Wage Council, with representation from the government, the private sector and labor unions and, given that many major unions have been co-opted by the government, it is even less likely that labor voices will triumph.

Economists in El Salvador have been clear that neoliberal policies Bukele has implemented over the past five years are at the root of a broader economic crisis the country is experiencing. In an interview at A Primera Vista on March 12, leftist economic expert Cesar Villalona identified major trends that are hitting the poor majority hardest, including a drop in production and exports, increased dependence on imports, low foreign investment, a reduction in public spending, high national debt, declining purchasing power and reduced currency circulation, and the collapse of the agricultural sector.

Low Production and Foreign Investment

On the state of the country’s production, Villalona says El Salvador is trending "towards stagnation in the production of goods and services... entering what is called a recessionary cycle, which is when production is less than potential." El Salvador’s Central Reserve Bank has determined that a 2.2% increase in production, already a small percentage compared to other nations, would meet the country’s goal to reach its productive potential. For the current year, however, the Central Reserve Bank projects just a 2% increase, while the IMF and World Bank forecast a 1.7% increase.

Referencing this limited economic growth, Villalona points to a lack of increase in the population’s purchasing power and a 7% reduction in currency circulation in 2023. He points to the drop in exports in the first quarter of this year as a result of Salvadoran products not performing well in U.S. and Central American markets.

Contrary to Bukele’s propaganda, boasting blooming foreign investment, his first five years were marked by a drop of 44% in direct foreign investment compared to the previous administration of Salvador Sánchez Cerén of the leftist FMLN party, according to the Central Reserve Bank.

One of the reasons foreign investment has dropped, offers Villalona, is that potential foreign investors are wary of political insecurity in the country, as “there is no rule of law here.” Bukele, now serving a second consecutive presidential term in violation of El Salvador's constitution, has taken control of all government branches through a series of judicial coups and a unilateral overhaul of the political system. Bukele’s party has overseen a drastic rollback in government transparency that had been improved under the previous FMLN administrations. Amid multiple accusations of corruption, especially in health care spending and public works, Bukele’s government sealed access to public information about government spending for seven years and passed legislation to protect officials accused of corruption.

Bukele’s party’s response to the drop in foreign direct investment, however, has been to double down on some of the hallmarks of neoliberal policy that defined the 1990s and 2000s under the leadership of the right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA), which led to widespread inequality and mass migration. In a bid to attract more foreign capital, in March 2024, the Legislative Assembly, controlled by Bukele’s Nuevas Ideas (New Ideas) party, approved a law eliminating income tax for all foreign investors.

The consequences of such a policy, warns Villalona, will further devastate El Salvador’s budget. “[The income tax] is the second most important [tax] after the value-added tax [or VAT, a steep tax on nearly all consumer goods and services]. Income tax accounts for 40%, and VAT accounts for 45% [of all tax collection in El Salvador].”

Rising Public Debt

Another major concern for Villalona and many other economists is the national debt, which has increased by 50% in the five years of Bukele’s presidency, from $19 billion in 2019 to nearly $29 billion as of March 2024. This debt represents payments owed to the pension system, international banks, national banks, and to bonds.

Notably - and inversely - while the national debt is rising rapidly, Bukele and his party have drastically slashed social spending, cutting key programs in healthcare, public education, and agriculture, among others. Consequently, unemployment in the public sector also continues to mount. Meanwhile, spending has risen in other sectors, notably government communications, policing and the Armed Forces.

The budget deficit, as of March 2024, was projected at $1.5 billion. Budget deficits were seen repeatedly throughout Bukele’s first term and to compensate for these shortfalls, the government has had to seek out additional loans or simply has been unable to execute wide swaths of the budget.

Budget shortfalls have contributed to illegal mass layoffs in the public sector and limitations on key public institutions. The fiscal crisis is so severe that even the National Directorate of Municipal Works, a department Bukele created to execute public works projects to bolster his public image, received approximately half of the funds designated to it in the budget, according to Villalona. Other sectors, namely institutions created by previous leftist administrations, have been targeted more intentionally, albeit in the name of austerity, like the Cultural Ministry, the Women’s Cities and the National Youth Institute, to name a few.

But one of the most alarming budget attacks has been on higher education. Due to the government’s failure to disburse funds allocated to the University of El Salvador (UES) in various budgets throughout Bukele’s presidency, it now owes the UES a whopping $52 million. This debt leaves the future of the country’s only public university - and a historic bastion of leftist student organizing - hanging in the balance as it’s set to finally reopen for in-person classes after being shuttered since the early days of the pandemic.

Another contributing factor to the overall economic crisis is the government’s mishandling of the pension system. A law passed by the right-wing ARENA party in 2006 permits the state to borrow from the Salvadoran Pensions Institute, formerly known as INPEP. When Bukele took office in 2019, the government already owed $4 billion to the pension system; since then, this debt has increased to $9 billion, more than doubling in just five years. Thanks to a reform to the pension system that Bukele’s Legislative Assembly passed in 2022, the government is not required to begin paying off the loans or their accumulated interest for four years, leading to tremendous uncertainty for the future.

Agro-Industry and Imports

As evidenced by the high food prices resulting from increased dependence on imports, Bukele’s policies have devastated the agricultural sector in particular. In 2020, Bukele eliminated five FMLN government programs that were designed to stimulate agricultural production, support local farmers and cooperatives, and help the country become more self-sufficient. As a result of those programs, such as the Family Agriculture Plan, production of staple food products and employment in the agricultural sector had dramatically increased under their governments (the other programs eliminated by Bukele’s government in 2020 were: the Family Agriculture for Municipalities in Extreme Poverty; Rural Development and Modernization; Community Care; and Amanecer Rural, “Rural Morning” in English). In 2020 the government also imported thousands of tons of corn at a cost of $13.50 a quintal instead of purchasing it from local farmers who sold it for $12. This year’s budget cut to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock, from $45 million – from $136.5 million in 2023 to $90.9 in 2024 – according to Equipo Maiz, is just the latest example of Bukele’s neglect for El Salvador’s agricultural sector.

This progress that had been achieved by previous FMLN governments has been largely reversed. In May 2019, before Bukele took office, the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock projected 84.62% self-sufficiency in the production of basic grains for that year, with corn production exceeding national demand. 2024 saw the lowest production of basic grains in the past seven years. Using debt money, Bukele has increased imports of basic foods significantly, benefitting importers, while the agricultural sector has seen a “zero growth rate in the last five years,” asserts Villalona. In a more recent interview, Villalona explains that in 2019, the total amount spent on agro-industrial products (includes crops as well as industrial food imports like processed foods - tomato sauces, flour for baking, etc.) imported to El Salvador was $11 million; in 2023, the total was $386 million. In parallel, the national agroindustrial sector has seen a dramatic loss of over 51,000 jobs within five years.

Taken together, Equipo Maiz warns of an incoming food crisis as prices for basic foods have increased while the population’s wages remain stagnant.

A Mounting Crisis

As the material challenges faced by the population worsen due to Bukele’s economic policies, public discontent grows, as does migration out of the country. Throughout the 20th century, powerful labor, campesino, student, and women’s movements confronted the Salvadoran oligarchy, and in the 21st century, opposed neoliberal policies and transnational corporations. These grassroots movements are clearly needed now to confront a new phase of rising inequality in the country. However, Bukele is attempting to submerge the population in fear through political persecution against grassroots leaders and widespread arbitrary arrests under the ongoing State of Exception.

The need for international solidarity, action from international organizations, and an end to U.S. complicity in the face of Bukele’s abuses of power are essential to supporting the movements that will be needed to tip the scales in favor of working people.

"I am a CISPES supporter because continuing to fight for social justice and a more people-centered country means continuing the dream and sacrifice of thousands of my fellow Salvadorans who died for that vision.” - Padre Carlos, New York City

"I am a CISPES supporter because continuing to fight for social justice and a more people-centered country means continuing the dream and sacrifice of thousands of my fellow Salvadorans who died for that vision.” - Padre Carlos, New York City