El Salvador Election Observation Report, January 18 elections

Municipal and Legislative Elections, January 18, 2009

by CISPES - Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador

Introduction

Members of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador (CISPES) took part in the Misión de Observación Internacional (MOI) to monitor the legislative and municipal elections in El Salvador on January 18th, 2009. The MOI was accredited by the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) and observed the entire election day process, from the installation of the voting tables to the final vote count. CISPES members observed in the municipality of San Salvador, San Salvador, and in the municipality of El Paraíso, Chalatenango. Observers monitored the electoral campaign and studied electoral laws and regulations in the weeks and months leading up to election day. During the week before the vote, CISPES members met with civil society organizations, other international observer missions, and government agencies such as the Human Rights Procurator’s Office (PDDH).

This report provides the results of CISPES' direct observation of the electoral process on the day of the vote and an analysis of the multiple factors that we believe impeded the country from achieving a fully free and transparent democratic process. This report is divided into sections:

1) The Role of Government Institutions

2) The Role of the Media

3) Dirty Campaign & Electoral Violence

4) Election Day Observation

5) Recommendations

The current electoral process in El Salvador was designed to ensure equal representation and participation from all of the political parties in the country. While intended to provide a high level of transparency, the electoral process has deteriorated significantly due to the failure of state institutions to fulfill their role in a nonpartisan manner. In the absence of a fair, nonpartisan institution to enforce the Salvadoran electoral code, the political parties with the most power and resources dominate the electoral process.

It is our analysis that the majority of impediments to a fair and transparent election that we observed and have included in this report can be attributed to this overarching institutional weakness — the absence of an impartial, nonpartisan regulatory body that monitors and guides the Salvadoran electoral process.

The report concludes with a set of recommendations intended to address the concerns outlined in the preceding sections. The goal of these recommendations is to further the implementation of the 1992 Peace Accords by increasing transparency and fairness while diminishing the influence of political parties and partisan state institutions over the results of future elections.

Chapter 1: The Role of Government Institutions

Composition of Supreme Electoral Tribunal

El Salvador's Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE) was established by the 1992 Peace Accords to be an unbiased arbiter of the country's elections. The TSE is charged with executing the electoral process, shaping and enforcing electoral law, and determining the electoral results. It oversees the Electoral Registry, political campaigns, the production and distribution of election materials, all election day procedures, and the counting of votes.

The TSE is composed of five magistrates. Each of the three largest political parties, as determined by the results of the most recent election, is represented by one magistrate. Currently, the right wing ARENA and PCN and the left wing FMLN each appoint one magistrate. The two remaining TSE members are nominated by the Supreme Court of Justice and confirmed by the Legislative Assembly. The appointees from the Supreme Court currently include one magistrate from the right and one from the left. Originally, decisions of the TSE required a consensus of four out of the five magistrates. However, the law was changed by the Legislative Assembly in 2005 to require only a simple majority of three magistrates. This change has allowed the right wing's three magistrates to make decisions about the electoral process without the consensus that was previously necessary.

A similar power imbalance favoring the right wing parties is found within every administrative body of the electoral structure: the 14 Departmental Electoral Boards (JED), 262 Municipal Electoral Boards (JEM), and 9,533 Vote Reception Boards (JRV). One representative each from ARENA, PCN, PDC and FMLN — the four parties that received the most votes in the last election — is given a seat on each of these boards. The fifth seat is allotted to either the CD or FDR. The resulting composition of these electoral boards inevitably favors the right wing with three out of five representatives, as the FMLN, CD and FDR are the only left/center political parties. As a result, the representatives of the right wing parties sitting on these boards can decide the outcome of disputes without seeking consensus from the left and center parties, as would be the case in a truly impartial electoral system.

Electoral Registry and DUIs

In December 2007, the Organization of American States (OAS) released an audit of the TSE and the Electoral Registry, which included over 100 recommendations to ensure a more accurate and transparent electoral process. Most pertinent to the integrity of the January 18th elections, the OAS found that the Unique Identification Document (DUI) system and the Electoral Registry were fraught with errors. The TSE discovered many irregularities including:

- Over 100,000 persons listed in the Registry, or 2.7%, are deceased.

- 330,000 names cannot be matched with a birth certificate.

- Over one million individuals have inaccurate information listed on their DUIs.

- 236,000 voters in the Registry that have DUIs do not appear in the 2007 government census.

In addition to the aforementioned problems, the OAS, civil society organizations, and multiple political parties have denounced the lack of transparency surrounding the Electoral Registry, specifically pointing out that it was not made available for scrutiny by all political parties and the general public. It appears that the governing ARENA party alone had full access to the Registry prior to the January 18th elections.

The TSE did not act upon the vast majority of the recommendations made by the OAS, and the OAS has not played an active role in applying pressure on the TSE to comply with its recommendations. The widespread discrepancies within the Electoral Registry and the DUI system create the possibility for technical fraud that is extremely difficult to detect on election day. The stated incongruities could:

- Hinder entitled individuals from casting their votes since they cannot properly identify themselves at the polls.

- Result in the disqualification of legitimate votes.

- Allow an individual to be registered and vote in a municipality that does not correspond to his or her residence.

- Allow individuals to obtain multiple DUIs under alias names and vote multiple times in various municipalities.

- Allow non-Salvadoran citizens to obtain DUIs and vote (a practice well-documented in previous elections, including those of 2004).

In our view, the numerous irregularities in the Electoral Registry and DUI system and the corresponding opportunities for widespread fraud compromise the ability of national and international observers to ascertain the validity of the voting process on election day.

Failure to prevent and respond to electoral violence

Another significant area of TSE purview is to monitor the entire electoral period. It is the duty of the TSE to ensure that the Electoral Code and Salvadoran law are respected by candidates throughout their campaigns, and that any violations are properly adjudicated. As documented in chapter 3, “Dirty Campaign and Political Violence,” clear infractions of electoral laws occurred throughout the campaign period, yet the TSE rarely investigated these instances.

Additionally, the TSE failed to take appropriate action against political violence during the campaign period. A number of formal denouncements were made concerning attacks against party activists, attacks carried out by activists against citizens, and other violent confrontations related to the campaign. The TSE did not adequately respond to these denouncements.

Furthermore, the TSE failed to take proactive steps to quell electoral violence. Instead, the Human Rights Procurator’s Office (PDDH) assumed this role and created a non-violence pact that was signed by every political party with the exception of ARENA. As the regulatory body in charge of the electoral process, the TSE should have created such a pact and sanctioned parties that violated it. Unfortunately, the PDDH cannot sanction parties for failure to comply with the non-violence pact, as the TSE is the only institution with the authority to enforce electoral laws.

From these observations, it is our belief that the TSE has not fulfilled its official obligation to regulate the Salvadoran electoral process. This failure undermines the transparency and legitimacy of El Salvador’s municipal and legislative elections of January 18, 2009, and, if repeated, could adversely affect the integrity of the upcoming Presidential election of March 15, 2009.

Public funds used for ARENA party campaign In May 2008, when El Salvador began to feel the effects of the international economic crisis, President Antonio Saca of El Salvador launched an "austere government" policy. According to the government, the goal of this policy was to cut back on some of the executive's expenses in order to continue to subsidize services such as electricity and gas to help Salvadorans cope with the economic crisis. To inform people about this policy, the government created a media campaign to publicize its austerity. However, the publicity ads that were created did not serve the purpose of educating the Salvadoran people about the current economic crisis – instead, they were used to further the ARENA party’s campaign for the 2009 municipal, legislative, and presidential elections, and to discredit the party’s main rival, the Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). Government television advertisements characterized President Saca as a man with "human sensitivity" and called on Salvadorans to be aware of the "dangers of populist government," a thinly veiled reference to the FMLN. The intended perception that the government was acting as a benefactor for those in need was countered when the online news site El Faro reported on the amount of money the government had spent on advertisements while its social spending decreased. According to El Faro, Saca’s government approved $7.4 million for its communication department in 2008. This amount is small compared with the money spent by this office in previous years. In 2005, the government expenditure for communications was $15.8 million. In 2006 the amount was increased to $17.4 million, and in 2007, the Saca government spent $23.4 million. After this information was released, the Foundation for the Study and Application of the Law (FESPAD) petitioned the Salvadoran government to release the total amount of government expenditures on publicity. Julio Rank, President Saca's Communications Secretary, responded that the government will not release budget details until after the 2009 elections. This decision has been highly criticized by civil society organizations as their demands for increased social spending have gone unanswered by the ruling party.

Role of the United States government

One component of our observation of the 2009 municipal and legislative elections was an examination of attempts by representatives of the United States government to influence the outcome of the elections. During the presidential elections of 2004, U.S. government intervention was a significant factor in persuading Salvadorans to vote for ARENA presidential candidate Antonio Saca. This intervention occurred in the form of threatening statements by U.S. officials, including former Ambassador Douglas Barclay, then-Undersecretary of State for Western Hemisphere Affairs Roger Noriega, and Representative Thomas Tancredo. U.S. Embassy staff reported to CISPES in June 2008 that many Salvadorans still fear that the 2004 threats are true, leading us to include them in this report on the January 2009 elections. Specific threats alleged that in the event of an FMLN presidential victory:

- Remittances sent to El Salvador by immigrants living in the U.S. would be cut off (3/18/04, El Diario de Hoy);

- Salvadoran immigrants living in the U.S. would be deported (El Diario de Hoy, http://www.elsalvador.com/especiales/2003/Elecciones2004/nota152.html);

- Temporary Protective Status (TPS), which provides legal residency to 200,000 Salvadorans in the U.S., would not be renewed (El Diario de Hoy, http://www.elsalvador.com/especiales/2003/elecciones2004/nota147.html).

Given the nature of the migration pattern that links the two nations, these statements carried a great deal of importance to Salvadorans residing in both countries. At the time, the number of Salvadorans living in the U.S. was estimated to be 2 million, and the remittances they sent back to their families amounted to almost $2 billion — thus representing the largest single component of El Salvador's GDP.

Furthermore, statements made by Barclay, Noriega, Tancredo, and others garnered substantial coverage in the Salvadoran press. This widespread media attention guaranteed that the majority of Salvadorans were aware of the stated consequences of voting for the FMLN, as declared by official representatives of the U.S. government.

Despite the false nature of these assertions, their validity remained unchallenged by the executive branch of the U.S. government throughout the course of El Salvador's 2004 electoral campaign. This institutional silence signified tacit support for the threatened changes in U.S. diplomatic relations and immigration policy tied to the outcome of the elections.

While the Bush Administration in Washington, along with its representatives at the Embassy in San Salvador, did nothing to counter the threats, some Members of Congress spoke out. U.S. Representatives Xavier Becerra and Raúl Grijalva held a press conference on March 16, 2004, to directly counter and debunk the threat that remittances to El Salvador could be cut off (3/17/2004, Diario Co-Latino). However, Salvadoran media coverage overwhelmingly privileged the original threat to remittances made by Representative Tancredo, while barely covering the counter-statement. (Centro de Intercambio y Solidaridad Final Report of 2004 Elections).

In the 2008-2009 campaign period, we have seen echoes of the same 2004 threats surrounding remittances and U.S. diplomatic relations. This time, the primary source of these threats is a Venezuela-based organization called Fuerza Solidaria that has carried out an extensive advertising campaign in El Salvador. Many of Fuerza Solidaria’s advertisements reiterate the threatening statements made by U.S. officials in 2004, even though those threats were later refuted by former Ambassador Barclay, though only after the election. Specifically, Fuerza Solidaria's ads allege that a Funes/FMLN victory would endanger the immigration status and ability to send remittances home for Salvadorans living the U.S.

A second message promulgated by Fuerza Solidaria through its advertising campaign states that ties between the FMLN and Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez will seriously jeopardize diplomatic relations between the U.S. and El Salvador if the FMLN performs well in the 2009 elections. One such TV ad features Dan Restrepo, advisor to U.S. President Barack Obama, stating that President Obama is extremely critical of President Chavez, and further intimating that the Venezuelan president is actively intervening in El Salvador’s politics. The ad then manipulates Restrepo’s words, suggesting that President Obama is concerned about the possibility of an FMLN president, who the U.S. supposedly expects will emulate the policies of President Chávez.

Early in the current campaign period, U.S. officials again made public statements that seem intended to defame the FMLN. In June 2008, Deputy Secretary of State John Negroponte and Ambassador Charles Glazer made public statements that tie the FMLN political party to the Colombian guerrilla force, Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) (3/16/2008, UpsideDown World http://upsidedownworld.org/main/content/view/1340/1/; 6/24/08 EcoDiario Online).

To date, no evidence has been put forward to support this allegation. Therefore, it can only be concluded that these statements were attempts to damage the reputation of the FMLN and provide yet another pretext for threatening that U.S.-Salvadoran relations would deteriorate under an FMLN government.

In addition to U.S. government officials passing judgment on the FMLN in a very public manner, the ARENA party itself has expressed a strong desire for the U.S. to take more action to prevent an FMLN victory in 2009. In a speech made at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., in September 2008, the ARENA-appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs, Marisol Argueta, asserted that the FMLN's bid for Presidency poses a concrete security risk for the U.S. and appealed to the U.S. to coordinate forces with the current Salvadoran government to stop the rise of another “populist government” in Latin America. Argueta’s comments represent an open plea for the U.S. to involve itself in El Salvador’s electoral politics, and thereby infringe on the political sovereignty of the Salvadoran people. This represents a clear violation of the Salvadoran Constitution.

Despite the incidents outlined in this section, it is difficult to assess the extent to which U.S. government involvement had an influence on the outcome of the January 2009 elections. Until three days before the January 18 elections, the State Department failed to issue public statements dispelling fears about remittances and immigration status, and assuring continued amicable relations between the two countries.

However, on January 16th, in his final press conference before being recalled as Ambassador, Charles Glazer declared that the relationship between the United Status and El Salvador would not change based on the outcome of the 2009 elections. He reaffirmed that the U.S. would assume a position of neutrality, irrespective of which party wins the presidency (3/16/2009, Prensa Gráfica). This statement represents the most appropriate position that the U.S. State Department could adopt — one of complete respect and neutrality with respect to the Salvadoran democratic process. This position would be strengthened if the new U.S. Ambassador to El Salvador were to make a similar public commitment soon after taking office, declaring specifically that the U.S. will neither intervene nor retaliate against whatever government is elected on March 15.

Chapter 2: The Role of the Media

Though there are numerous alternative media outlets in El Salvador, providing news in both print and broadcast forms, the vast majority of Salvadoran households receive their news from a handful of mainstream media sources. For this reason, our report focuses on campaign coverage in the mainstream media, with specific emphasis on the two daily, nationally-circulated newspapers, El Diario de Hoy and La Prensa Gráfica.

A 2003 study on newspaper readership in El Salvador, commissioned by La Prensa Grafica, provides a snapshot of the dominance of these mainstream sources. The study found that 92% of homes that read a newspaper read La Prensa, El Diario de Hoy, or both. Meanwhile, only 12% of homes read another publication.

The companies that own La Prensa Grafica and El Diario de Hoy also own or are affiliated with other media outlets in El Salvador, including both print and broadcast sources. For example, Grupo Dutriz, which publishes La Prensa Grafica, also publishes several magazines, and has links on its website to several other Salvadoran media corporations, including Radio Corporación FM, which owns six radio stations in the country, Grupo Megavisión – operating seven radio and two television stations – and Tecnovisión, which owns TV channel 33.

Because of the high concentration of media ownership and editorial content sharing in El Salvador, and due to the greater accuracy possible in a study of the content of print media, this report focuses its attention on the two daily newspapers, and tentatively infers similar conclusions about broadcast media based upon these examples.

CISPES and other international and domestic election observation missions that actively monitored El Salvador’s media leading up the January 18th legislative and municipal elections determined that the media played an important role in shaping public perception of the political and electoral climate.

Through our own observations and through meetings with other observation missions and Salvadoran civil society organizations, we narrowed our findings to three conclusions:

- The mainstream media’s coverage of the elections focused on violence, unsubstantiated accusations made by political parties, and opinion polls, thereby distracting from real campaign issues and the contending parties’ policy proposals.

- The coverage provided to El Salvador’s two most important political parties, ARENA and the FMLN, was imbalanced in both the quantity and tone of reporting.

- The press failed to adequately investigate a number of serious accusations made by politicians and government entities over the course of the campaign, instead allowing such claims to go unquestioned in the public eye.

Focus on public opinion polls rather than campaign platforms and issues

In the months leading up to the January elections, campaign coverage by the mainstream press was complicit in suppressing public debate about platforms and candidates' policies. Instead of opening up dialog about campaign proposals and investigating politicians’ promises, the mainstream print media created a battle of opinion polls and focused on shaping public perceptions of the political parties themselves.

Manipulation of poll results was a key strategy of the press in projecting a strong image for the ARENA party, whose support was dwindling according to non-partisan polls. Although the FMLN presidential candidate, Mauricio Funes, had maintained a consistent 14-17 point lead over ARENA's Rodrigo Ávila, El Diario de Hoy attempted to project a turn in the presidential campaign on December 16th, 2008. El Diario highlighted a new Borges & Associates poll that showed Funes to have only a 5.3% lead – although the article did admit a 10% margin of error, thus resulting in numbers remarkably close to all previous polls.

For its part, La Prensa Grafica engaged in creating its own polls and publicizing its own findings. On December 23rd, 2008, La Prensa issued an extensive poll about the presidential candidates. Questions posed to the public were based only on perception, asking about each presidential and vice-presidential candidate: “What is your opinion of [candidate]? Good or bad?” After the initial report on its own poll's findings, La Prensa followed up the next day with an account of the reactions of various political figures to those findings. Most prominently covered was the analysis of Salvadoran President Tony Saca, of the ARENA party, who stated that despite poll findings to the contrary, ARENA would in fact win the presidency and the San Salvador mayoral race.

La Prensa and El Diario consistently placed greater emphasis on opinion than actual evidence, thereby misinforming the public and encouraging false perceptions of the political climate. By taking debate away from issues and focusing on the credibility of different polling mechanisms, the press reduced campaign coverage to predictions from those watching polling numbers, rather than focusing on the actual content of the campaigns.

The Salvadoran Human Rights Procurator's office commented on the media’s campaign coverage and its effect on campaign discourse, calling on the media to encourage educated voting rather than following trails of propaganda. It is undeniable that the Salvadoran mainstream press played a powerful role in limiting campaign coverage to a prescribed set of concerns that had little to do with the actual platforms and abilities of candidates.

Sensationalization of electoral violence

During the 2009 municipal and legislative campaigns, El Salvador’s mainstream media outlets over-emphasized the phenomenon of electoral violence, with the result of creating fear among the electorate. Similarly, unverified reports and accusations of the potential for violent action on the part of groups affiliated with the FMLN party were routinely reported on without further investigation, while violent attacks and assassinations of FMLN activists were not reported upon (see Chapter 3 of this report).

As of January 14, four days before the elections, the office of El Salvador’s Human Rights Procurator (PDDH) had received only 13 complaints of instances of electoral violence, which it defines as an act of violence that seeks to influence the elections, or involves actors who are part of the electoral process. In the 2006 campaign, the PDDH investigated 73 instances of electoral violence.

Despite a stark decrease in electoral violence between election cycles, the media’s reporting of such violence remained at an exaggerated level. Gerardo Alegría, the PDDH's Adjunct Procurator for Civil and Individual Rights – who is in charge of the institution's election monitoring efforts – referred to this media coverage as “propaganda” that incites fear and further violence. Furthermore, according to Alegría, the media's coverage of violence is specifically targeted at one specific party, presumably the FMLN, for which it is politically damaging to be repeatedly associated with violence.

Disproporionate and slanted campaign coverage

On January 14th, Luis Yáñez-Barnuevo, head of the European Union Observer Mission to El Salvador, told the online news source Elfaro.net that 70 to 80% of the total Salvadoran media coverage was in favor of ARENA and anti-FMLN. He elaborated that this uneven coverage was not limited to editorials, but endemic in the actual news pages. Yáñez-Barnuevo stated that “the information that [the media gives] about one political party is much more extensive, much more positive, and for the other side is smaller and more negative.”

In order to demonstrate the mainstream media’s active support of ARENA’s campaign, we conducted a survey of El Salvador’s two national newspapers, La Prensa Grafica and El Diario de Hoy, on Friday, January 9 – just 9 days before the municipal and legislative elections. We surveyed the content, tone, and quantity of coverage, and focused on articles that could have an impact on voters’ perceptions of political parties.

Jan. 9 2009: El Diario de Hoy

El Diario de Hoy’s election coverage on January 9focused almost exclusively on the broad theme of electoral violence. Two articles specifically link the FMLN with gangs. Two other articles cover the FMLN’s alleged training of armed groups – an unproven allegation that first surfaced in mid-December – without offering any evidence of the existence or nature of the groups.

A large photo published to support these articles – which depicts a group of young people standing in a plaza in front of an FMLN sign, wearing military fatigues and holding guns – had previously been published in December as proof of the existence of armed groups of youths who are trained by the FMLN. However, it was promptly revealed at that time that the photo actually depicts an annual community ceremony in the town of Dimas Rodríguez in honor of the town’s namesake, who was an FMLN leader during El Salvador’s civil war. The guns are toys. Nevertheless, the photo was reprinted on January 9 with the caption “The Armed Forces’ latest discoveries contribute to the case being put together by the police and the Attorney General.”

Another article documents the Supreme Court's investigation of a youth accused of wounding an ARENA party activist and two police officers. Without offering any evidence to support the Court's claim, the article reveals that the Supreme Court suspects this youth of being a gang member. While the article’s headline identifies the youth as being involved in the FMLN, the text of the article does not make a single mention of this point, let alone offer any evidence to back it up.

In total, El Diario contained seven pages of election coverage, which featured six articles about electoral violence. Of these six articles, five specifically accuse the FMLN of links to organized violence.

Jan. 9 2009: La Prensa Gráfica

In two of its 13 articles pertaining to the elections or campaigns, La Prensa continues to publicize allegations of FMLN gang connections, quoting President Tony Saca as saying “I have no doubt that there are gang members in the FMLN.” Across a two page spread, the quote is printed three times: once in large print at the top of the page, in a summary box across the bottom of the page, and again in an article headlined “Saca reaffirms that the FMLN uses gang members.” The same quote appears in El Diario on the same day. In other electoral news, La Prensa uses FMLN representatives’ varied predictions for fraud as evidence of divisions within the party. On the same page is the campaign update for ARENA’s San Salvador mayoral candidate, Norman Quijano. Unlike the coverage of the FMLN, which focuses on accusations aimed at the party and its subsequent rebuttals, this article actually covers a Quijano platform proposal. The article explains that Quijano has secured financing for neighborhood development projects and ends with a reminder that ARENA presidential candidate Rodrigo Ávila supports Quijano’s campaign. While the FMLN is associated with hearsay and division, ARENA is depicted as having definite plans and party unity.

Insufficient investigation of political accusations

In the months leading up to the January elections, three key claims against the FMLN received extensive coverage in the mainstream press. However, the very news outlets that reported on these claims failed to carry out effective investigations into their veracity. The claims focused on connecting the FMLN to warfare and crime, thus exploiting the party's roots as a guerrilla force to cultivate distrust and fear of the party.

Accusation 1: FMLN linked to FARC

As early as May 2008, the press was quick to jump on a claim that the FMLN was involved with Colombia's FARC rebels. This accusation surfaced after a laptop computer was recovered from a FARC outpost in Ecuador. The case was never resolved, in spite of President Saca’s promise that the Attorney General was carrying out an investigation. As late as November 6th, 2008, El Diario de Hoy continued to report on alleged connections between the FARC and the FMLN, this time based on claims made by the Venezuelan organization Fuerza Solidaria. The published accusations were never proven, nor rescinded.

Accusation 2: FMLN training armed groups

On December 13th,2008, El Diario de Hoy broke a cover story with the headline “FMLN Sponsors Armed Groups,” alleging that the FMLN party was carrying out military exercises in forty locations around El Salvador. El Diario sited three different government officials asserting evidence of these claims, and displayed photos of a group of young people wearing fatigues and holding weapons in formation before a platform of seated FMLN officials. As stated earlier in this section of this report, this photo was quickly demonstrated to have been taken at a commemorative ceremony. The press publicized this information, but did not back down from the condemnation that followed via headlines calling for investigation and then admonishment of the FMLN for involving youth in any sort of “military practice.”

Even though widespread public opinion held that the accusations of the FMLN's involvement with armed groups were “pure campaign tactics,” and well after the true origin of the tell-tale photograph was revealed, the photo continued to appear in the press. Calls for a government investigation into the armed groups – coming from churches, the Attorney General, and even the FMLN itself – have yet to be answered.

Luis Yáñez-Barnuevo, head of the European Union's observation mission, declared that the governments’ armed groups allegations amounted to electoral tactic. El Diaro de Hoy and La Prensa Grafica failed to report on this statement.

Accusation 3: FMLN working with gang members

On January 7th, 2009, the director of the National Civilian Police made a press statement that gang involvement had been detected within political parties, but declined to state which parties. This created space for ARENA director Ricardo Martínez to be quoted as saying, “The population knows who is the violent party.” On the following day, El Diario de Hoy headlined a statement by the Attorney General: “Activists say that they are gang members and with the FMLN.” In the accompanying article, the Attorney General goes on to say that the investigation of this claim had begun, but the claim was not yet proven.

The article was accompanied by a close-up photo of a young man with a tattoo across his forehead, wearing an FMLN bandana. It is not clear from the article or caption who this man is, nor why his photo was published. A smaller photo shows the six youths who were actually detained in Santo Tomás, none of whom are wearing tattoos or FMLN insignias. Later, all of the youth were released without charges, save for one whose case has been indefinitely stalled.

In each of the three cases cited in this section, defamation of the FMLN by government sources quickly made headlines in the mainstream media. In all three instances, the press failed to investigate the accusations, yet continued to report upon them nonetheless.

Chapter 3: Dirty Campaign and Electoral Violence

While receiving a disproportionate amount of positive media coverage for its campaign, the ARENA party embarked on a parallel, offensive campaign (or “dirty campaign”) aimed at discrediting and demoralizing the FMLN and its supporters by:

- Repeatedly making unfounded accusations of FMLN links to violent groups, including including urban gangs and “armed groups” in the Salvadoran countryside;

- Propagating fear by deploying a military presence in communities that serve as active, organized centers of support for the FMLN; and

- Tacitly condoning violent attacks against FMLN activists by refusing to acknowledge and investigate politicly-motivated assassinations of leaders, organizers, and sympathizers of the FMLN.

As mentioned in the previous section, the mainstream press gave extensive coverage to claims coming from the government and ARENA party against the FMLN - but failed to carry out effective investigations into their veracity - in the months leading up to the January elections.

Salvadoran government agencies such as the Minister of Security, the Attorney General, and the National Civilian Police, have bolstered ARENA’s campaign rhetoric by corroborating unfounded speculations about the FMLN from their official positions within government.

The Dirty Campaign

A pervasive campaign of anti-FMLN television ads and leaflets has been funded and distributed throughout El Salvador by Fuerza Solidaria, a Venezuelan organization committed to stopping the FMLN from winning the election. The president of Fuerza Solidaria, Alejandro Peña Esclusa, is a right wing politician who lost to Hugo Chavez in Venezuela’s 1998 elections. Fuerza Solidaria has spent over $700,000 designing and distributing electoral propaganda in El Salvador. Early on, Fuerza Solidaria attempted to convince voters that Chavez was funding the FMLN campaign. Ads stated that an FMLN victory would threaten relations with the U.S. government and endanger remittances – the money sent home by Salvadorans living in the U.S. The ads also implied that an FMLN victory would threaten Temporary Protective Status (TPS), which allows over 200,000 Salvadorans to remain in the U.S. legally.

Midway through the campaign, Fuerza Solidarida and the right wing’s efforts shifted from connecting the FMLN to FARC and Chavez to publicizing the Salvadoran Ministry of Defense’s unsubstantiated claim of an FMLN connection to “armed groups” in the Salvadoran countryside.

While President Saca initially expressed the need for a joint investigation by the Salvadoran Attorney General’s Office, the United States’ Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), Interpol, the Organization of American States (OAS), and the United Nations (UN), he later retracted this proposal, saying that the government would proceed with the investigation internally. The media has not suspended its reporting on the matter, however, leading observers – including the OAS – to dismiss the ARENA party’s allegations as mere electoral propaganda that could have dangerous repercussions and serve to incite political violence.

The Defense Minister’s announcement also served to justify the deployment of military troops throughout the area surrounding El Paisnal to monitor these supposed armed groups. In response, organizations in El Papaturro, Canton, La Bermuda, Suchitoto, and elsewhere in the department of Cuscatlán mobilized to denounce the presence of soldiers in their communities. According to Jose Antonio Rivera, a representative of the El Papaturro community, the presence of soldiers is viewed as a “very delicate” provocation and blatant violation of the 1992 Peace Accords, which prohibit the armed forces from being used for domestic law enforcement. “We want the authorities to stop implicating communities that have nothing to do with these false accusations,” said Rivera.

To buttress of the government’s false accusations, Fuerza Solidarida ran a new series of advertisements that used a simple flow chart to connect the FMLN to armed groups, including the tag line, “A vote for Mauricio is a vote for danger.”

The false connection of the FMLN to gangs has emerged as another tactic of the right wing’s dirty campaign strategy. Again, the National Civilian Police, ARENA party, and Attorney General’s Office have validated these claims without further investigation or legal proceedings, though the FMLN has called for such steps.

Wednesday, January 14th, marked the official close of electoral campaigning. Two days after this date, however, leaflets produced by Fuerza Solidariai that assailed Mauricio Funes as a “pro death” candidate, referring to his implied views on reproductive rights, were distributed door-to-door in San Salvador. Furthermore, Fuerza Solidaria has been conducting captive audience meetings with various business' employees throughout El Salvador. The meetings feature a 17-minute video and a longer presentation by Peña Esclusa that implores employees to vote against the FMLN. Fuerza Solidarida’s actions violate two Salvadoran Election Laws, one stating that non-political parties are not authorized do campaign work; and two, all campaign work must stop at midnight three days before the election.

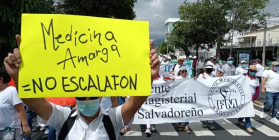

Electoral Violence

By publicly stating that FMLN supporters are affiliated with gangs and armed groups, ARENA has sought to justify verbal and physical attacks on the FMLN.

On January 9, 2009, the eve of the arrival of the CISPES' Election Monitoring Delegation in El Salvador and just five days before the close of the campaigns to elect municipal mayors and legislative deputies, two FMLN activists were assassinated. 63 year-old Delfo de Jesús Rodríguez and his 26 year-old son, Maximino Rodríguez, were murdered in their home in Las Minitas by a group of six heavily armed men dressed as police officers and wearing ski masks. The manner of the assassinations, in which the armed men indiscriminately shot into the Rodríguez house, killing the father and son, is reminiscent of the death squad killings that were prevalent during El Salvador’s 1980-1992 civil war.

Two days later, during a campaign rally in the town of Jiquilisco, Usulután, FMLN supporters gathered at the main entrance of the municipality and planned to march to the center of the city. When the group passed by ARENA headquarters, members of ARENA shot tear gas into the crowd, sending 15 people to the national hospital of Jiquilisco. Of the people who were seriously affected, most were children and the elderly — two were pregnant women.

The day after the attacks in Jiquilisco, in the capital city of San Salvador, campaigners for ARENA mayoral candidate Norman Quijano threw rocks at FMLN San Salvador mayor Violeta Menjívar and members of her contingent during a campaign stop. The conflict that resulted ended in ARENA members opening fire on Menjívar’s campaigners, injuring four people. Quijano has publicly stated that his campaigners are armed and should be “considered dangerous.”

These assassinations and acts of violence have two main themes in common. The first is that the victims are all leftist political activists. The second is that government officials have failed to conduct proper investigations into these cases. The cases have received no acknowledgement from the National Civilian Police or the Supreme Electoral Tribunal, no investigation from the Attorney General’s Office, and no coverage by major news networks.

We’ve concluded that the ARENA party is intentionally creating a political environment reminiscent of the civil war of the 1980s – a “fear campaign” – to silence political activists on the left and to suppress popular support for the FMLN.

Chapter 4: Election Day Observation

On election day, CISPES activists participated in the Misión de Observación Internacional (MOI), which that was composed of 75 observers from Spain, the United States, Sweden, Argentina, Italy, Switzerland, and Germany. The observers were present in 10 municipalities in the departments of San Salvador, Sonsonate, Chalatenango, Cuscatlán, La Paz, and La Libertad. All observers were present at their assigned Voting Centers from the time the centers opened for installation until after the final count had taken place. In addition to its own observation efforts, the mission received denouncements from Salvadoran citizens about anomalies observed during election day.

Through first-hand observation and receiving citizen denouncements, the MOI found two main areas of irregularities that impeded the free, fair, and transparent execution of the electoral process in El Salvador.

Polling place problems

Violations of the Electoral Code and Salvadoran law by members of the Voting Tables (JRVs), Municipal Election Boards, and voters that took place within Voting Centers on election day were prevalent. The following anomalies were observed:

- None of the observed Voting Centers opened on time.

- In many cases, members of the Municipal Election Boards and presidents of JRVs did not inspect the credentials of Voting Table members.

- On several occasions, the package containing the electoral materials was given to the JRVs by members of political parties that were not part of the Municipal Election Board.

- Overall, a general confusion was observed among JRV members concerning their roles and responsibilities. Often, members would carry out responsibilities of other members, or political party Vigilantes would take on the roles of the JRV members.

- In most cases, JRV presidents did not inspect the hands of voters to verify that they were not marked with ink, which would have assured that they had not already voted.

- Many JRV secretaries signed, sealed, and tore off the corners of the ballots at the beginning of the day instead of waiting to do so immediately prior to handing them out to each voter.

- Electoral propaganda and campaign rallies were observed within many Voting Centers.

- On several occasions, political party Vigilantes or an unidentified second person was seen in the voting booth with a voter.

- Some Voting Centers closed early, prior to 5:00 PM.

- Several Voting Centers did not have sufficient lighting to ensure a correct final count of ballots.

All of these observed irregularities threaten the validity of the voting process carried out on election day. They resulted in citizens not being able to vote, voters not being able to cast their ballots without the interference of electoral propaganda and third-party interference, and potential for mistakes or intentional fraud during the installation of the voting tables and counting of the votes.

Institutional problems

The second type of irregularity observed and denounced by citizens on election day represents a far greater and deeper technical fraud that was carried out prior to election day. The following was observed or denounced by citizens:

- The Electoral Registry was often denounced for not reflecting the actual population of a municipality. For example in El Paraíso, Chalatenango, residents informed observers that the Electoral Registry contained 7,000 entries, even though the municipality only had 4,000 residents.

- Many voters were observed voting with Unique Identity Documents (DUIs - the ID card used for voting) that presented irregularities. For example, contradictions between the place of residence on the DUI and on the Electoral Registry, damaged DUIs that could not be verified, differences between the photo on the DUI and on the Electoral Registry, an overwhelming number of brand-new DUIs (observed in El Paraíso, Chalatenango), and seemingly false DUIs.

- Many citizens denounced the presence of people from other countries (primarily Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua) participating in the electoral process. In El Paraíso, Chalatenango, residents denounced the presence of foreigners working as members of the JRVs and also being transported by bus into the municipality to vote. In San Isidro, Cabañas, residents, with the backing of four political parties (the FMLN, PDC, PCN, and CD) closed down the Voting Center due to the overwhelming presence of foreigners in their municipality on election day. This, combined with the presence of a large number of deceased individuals on the Voter Registry, raised the concern that foreigners had arrived to vote using the identities of dead people.

- In the municipality of San Salvador, it was denounced that a large number of people were present in the ANDA building (near the National University Voting Center) and a militant of the ARENA party was distributing DUIs to them so they could vote a second time. This incident was reported in sufficient time for the police to detain those involved. The detainees later confessed that they had already voted in the municipality of Rosario de Mora and were being directed to vote again.

- The day before election day (Saturday, January 17, 2009), it was denounced that two trucks full of people arrived at the Vice-Ministry of Transport's building in San Salvador, which should be closed on weekends. The people reportedly entered the building and later mattresses were brought, raising suspicion that people who were not residents of San Salvador were being housed there to vote the next day. Observers arrived and asked security guards for permission to enter. Access to the building was denied, and observers were told that the building was closed on weekends and no one was inside.

These irregularities all point to a more insidious attempt at fraud. The problems with the Electoral Registry, the presence of false and suspicious DUIs, the numbers of people being bussed around the country, and the presence of foreigners on election day together subvert the will of the Salvadoran people to elect their preferred candidates.

Chapter 5: Recommendations

- The TSE should grant all political parties and the general public full access to the Electoral Registry for inspection and audit, specifically with respect to the official population data of the National Registry of Naturalized Persons (RNPN).

- The Electoral Registry should be purged and updated in accordance with the most recent 2007 Population Census, as recommended by the Organization of American States.

- As the foremost regulatory body of the elections, the TSE should increase its efforts to prevent, investigate, and penalize violations of the Electoral Code. Violations during the campaign and on election day should be punished in accordance with Salvadoran law, and violations of the Code on election day should be stopped. Many serious denouncements made to the TSE were dismissed without sufficient investigation, which led to major breakdowns of the electoral process — most notably in the case of San Isidro, Cabañas.

- The TSE should denounce and investigate all charges of campaign-related violence, and take active steps to prevent further electoral violence. It is the duty of this body to demand that the campaign progress in a peaceful manner and to penalize the political parties that do not cooperate.

- Recognizing the significant role played by the media throughout the campaign, the TSE should call for well-researched and informative electoral coverage, instead of sensationalized coverage that serves to polarize, generate fear among the population, and favor one political party.

- Residential Voting should be expanded to the national level and implemented in such a manner that provides the entire population convenient access to community voting centers, thus encouraging voter turnout among legitimate residents and discouraging non-residents from voting illegally.

- All JRV members and party vigilantes should receive a thorough, standardized training in all of the procedures, regulations and laws governing their positions and the electoral process.

"I am a CISPES supporter because continuing to fight for social justice and a more people-centered country means continuing the dream and sacrifice of thousands of my fellow Salvadorans who died for that vision.” - Padre Carlos, New York City

"I am a CISPES supporter because continuing to fight for social justice and a more people-centered country means continuing the dream and sacrifice of thousands of my fellow Salvadorans who died for that vision.” - Padre Carlos, New York City