Social movement leaders arrested in context of State of Exception

Since May, there has been an alarming trend of social movement leaders being arbitrarily arrested in the context of the nationwide State of Exception. Under the State of Exception, which was approved on March 27 for a 30-day period, but which has already been extended twice, raising concerns that the Bukele administration seeks to maintain its expanded power in perpetuity, constitutional rights such as the right to due process and the right to defense are suspended. A person can be arrested without a warrant and held for up to 15 days without charges being presented.

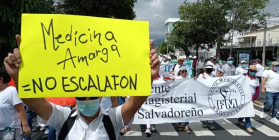

In May, the police captured a number of people linked to social and popular organizations, including Geovanni Guerrero, a union member from the San Salvador municipal office, who, notably, participated in the May 1 International Workers Day march. Geovanni is also a member of the Popular Resistance and Rebellion Bloc (BRP), which called for his immediate release. Other cases include Dolores Almendaris, the General Secretary of the Union of Workers of the Cuscatancingo Municipal Office (SETRAMUC) and Leticia Martínez, war veteran and member of the Association of Women Veterans of the Civil War of El Salvador.

According to official government data, between March 26 and May 8, 26,755 people were captured for alleged gang links, including 3,000 women and approximately 16,000 people under the age of 30, and 1,080 minors. Of this group of detainees, only about 200 people were released.

As of June 5, the government reports that the total number of people arrested has since risen to over 37,000. As news outlet Gato Encerrado has reported, the number of people incarcerated in El Salvador has doubled within the span of less than three months.

The detainees include students, working class people, people with developmental disabilities, and senior citizens. In addition, according to a report presented by Human Rights Watch and Cristosal in early May, “a growing body of evidence indicates that Salvadoran authorities have committed serious human rights violations since the emergency regime was adopted,” including arbitrary detentions, short-term forced disappearances, and deaths in custody. Amnesty International has shared reports that 18 people have died in custody.

As of June 3, a group of Salvadoran human rights organizations published data summarizing over 1,000 reports of human rights violations they have received during the State of Emergency. The vast majority of reports are of arbitrary arrests, followed by in-home raids and abuse of force by police and military.

It appears that many arrests have occurred without distinguishing between innocent and guilty; testimonies from relatives of detainees suggest that many of the arrests appear to be based solely on the criteria of being young people, students, or working-class people living in marginalized neighborhoods who have been stigmatized by security forces.

Accordingly, Amnesty International has called on President Nayib Bukele “to take all necessary measures to put an immediate end to the human rights violations taking place in the context of the emergency regime, and to design public security strategies that guarantee fundamental rights,” and launched an urgent action campaign to support this call.

The Salvadoran legislature initially approved President Bukele’s request to declare a State of Exception in response to a spike in homicides at the end of March, when more than 80 people were killed in a single weekend. Recently, online news outlet El Faro published a series of audio recordings that have been attributed to the government’s Director of Social Fabric, Carlos Marroquín, and that suggest that the murders occurred in response to a rupture of an alleged pact between the government and the MS-13 gang that had maintained homicides at lower levels.

Despite the cries for alarm and significant international media coverage, Salvadoran social movement leaders say Bukele’s policies continue to victimize people living in areas historically abandoned by the State and institutionalize both state violence and high levels of impunity for state aggressions against the population. Beyond serving as a smokescreen for the widespread criticism of Bukele’s Bitcoin policy, they say, the State of Exception, with its broad and excessive use of police and military force, aims to sow fear among the people the government claims to protect.

In addition to directing more financial resources to the army and police, the Legislative Assembly, dominated by Bukele’s New Ideas party and allies, approved a flurry of sweeping legal reforms, ostensibly to further crack down on gangs, including increased sentences for children as young as 12 and the elimination of a two-year limit on provisional detention, meaning the government can now keep people in jail for years without presenting charges or scheduling a hearing.

The legislature also approved a terrifying new gag law making it illegal to reproduce statements made by, or presumed to be made by, gangs, thus potentially criminalizing journalists or media outlets for even reporting on the issue. The Salvadoran Association of Journalists (APES), accompanied by human rights organizations, is challenging the law in court, though without high hopes given that New Ideas legislators unlawfully installed the current members of the Constitutional Chamber immediately after taking office in May 2021.

In this sense, say social and popular movement leaders, the arrests being carried out within the context of the State of Exception are also aimed at exercising greater control over the population, especially those who are decrying current injustices in the country.

"I am a CISPES supporter because continuing to fight for social justice and a more people-centered country means continuing the dream and sacrifice of thousands of my fellow Salvadorans who died for that vision.” - Padre Carlos, New York City

"I am a CISPES supporter because continuing to fight for social justice and a more people-centered country means continuing the dream and sacrifice of thousands of my fellow Salvadorans who died for that vision.” - Padre Carlos, New York City